[ad_1]

“Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through the links below.”

In our rule-free, anything’s-a-trend world, you’d think the last thing we need is a book telling women how to get dressed.

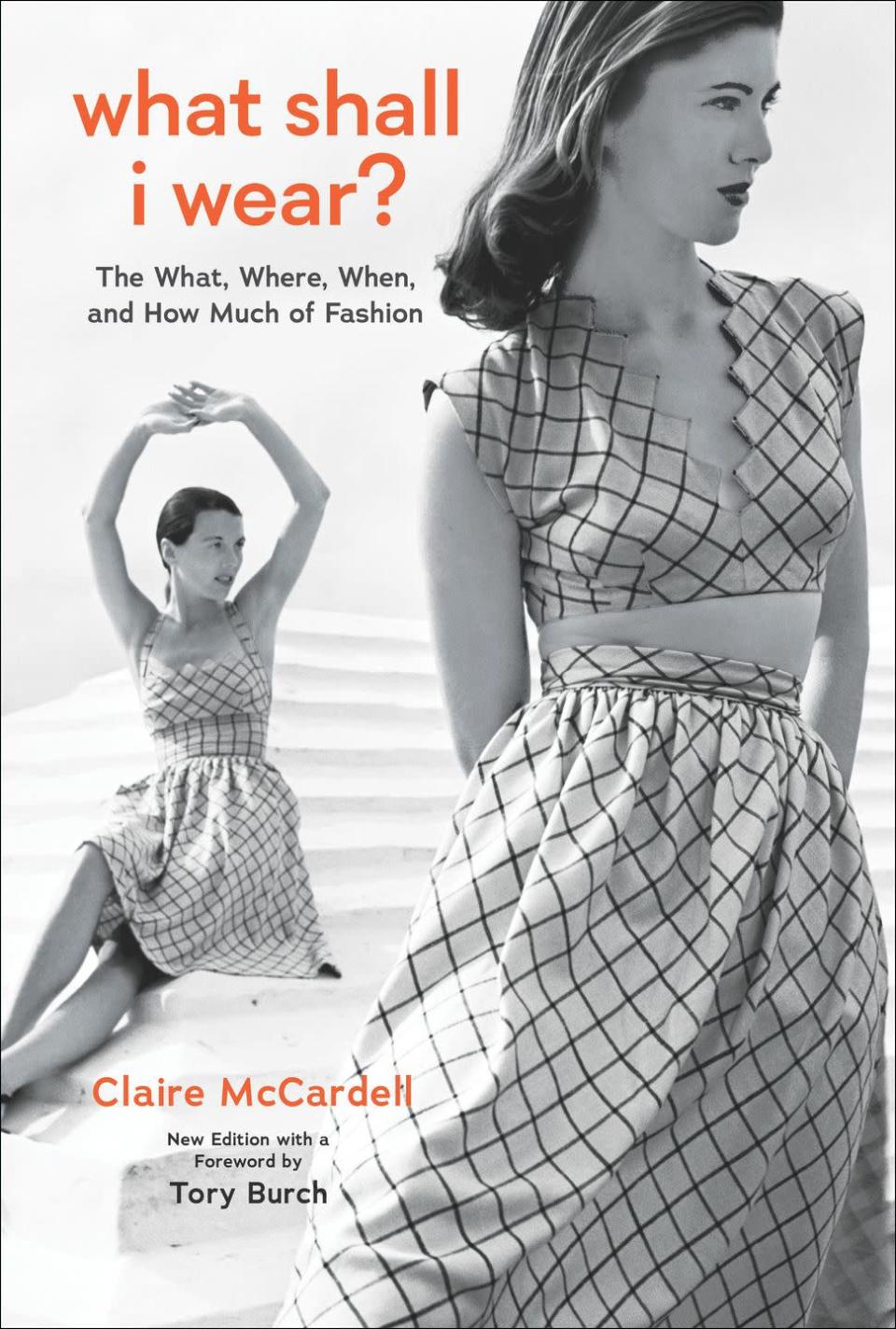

And yet! Claire McCardell’s What Shall I Wear? The What, Where, When, and How Much of Fashion, a witty and slender book first released in 1957 and now back in print with an introduction by Tory Burch, is the best and most considerate fashion book I’ve read this year.

McCardell was an American designer during an era most armchair historians tend to associate with the couture glories of Paris. And her name may not be as recognizable as fellow Americans Calvin Klein, Ralph Lauren, or Donna Karan. But the designs she created in the 1940s and ’50s, before she died of colon cancer in 1957, were some of fashion’s most revolutionary. Spaghetti straps, the ballet flat, and pockets and zippers on dresses were all McCardell innovations.

“What’s so fascinating is that 75 years after the fact, it does look so relevant for how women want to dress,” reflects Burch. “It’s really interesting, the way she gave women the ability to be unencumbered and free, [but also] to look at fashion more as an individual. That was something that I really admire.”

In her book, McCardell is part fashion philosopher, part industry hand, and part style guru. Coincidentally, her words read as a kind of sustainable fashion bible (even though changes in manufacturing and innovations in synthetics mean that a “cheap” dress from her era is much more liable to last than a “cheap” one from today). Most delightfully—frankly, most powerfully—she urges women not to adopt a position of anti-fashion or fashion skeptic, the pose popular today that encourages women to excuse themselves fully from appreciating fashion’s whims, trends, and beauty.

“I shall urge you to be brave,” she writes, after a sobering few pages exploring fashion’s frivolities. “Look at new fashions and see if they can be yours. Test the way they fit, feel, look—how they are supposed to be worn—how you will wear them. You’ll find you have enormous choice…. Explore Fashion and say No if you are temperamentally incapable of starting a trend.”

McCardell’s work, like her wisdom, had a truly singular mix of pragmatism and glamour. “She always thought about women,” says Burch. “She was an incredible feminist before feminism was really mainstream.” She had a way of using geometric lines and plaids to create flattering dynamism; her sense of color was understated but strong, declarative. Her shapes were joyful but never ridiculous. She had the confidence to be straightforward.

Burch is a McCardellite through and through. After first coming across the designer’s work in her art history studies at the University of Pennsylvania, she found herself thinking about her again when her husband, Pierre-Yves Roussel, took over as CEO in 2019. “I gave up that title and role, and was able to actually have some time to think about design,” she explains. “I wanted to try to make it a little more personal to me.”

McCardell was one of the first figures who came to mind. For her Spring 2022 collection, she created a handful of gingham and plaid dresses made in homage to McCardell, with a fitted waist and pleated skirt in a breezy silk. It’s one of the few dresses I have tried on in the past several years that has fit me like a glove, requiring no trips to the tailor, and actually making me look better instead of merely cooler—as I put it to Burch, when I put it on, I feel as though it enhances me. (She continued the design for the fall season.)

The reason for this was McCardell’s own inherent modernity. Her designs were feminine and occasionally romantic, but mostly they were strong and versatile. High fashion designers now too rarely think about how fabrics and silhouettes might complement or fit into a woman’s life, instead focusing on commerciality or wild creativity. “She wasn’t looking to couture in Paris,” says Burch. “In fact, they were looking at her. And she was going against every stereotype, every norm, and borrowing from sport. And also from menswear—I’ve always been fascinated with that feminine-masculine idea of what it means to create your own style.”

Burch, too, admires McCardell’s emphasis on working with rather than around (or even oblivious to) a woman’s body: “Her designs,” she explains, “were celebrating a woman’s body. She was saying that some things work for you and some things don’t.”

Perhaps McCardell’s most relevant legacy is the fact that she wrote a book at all. McCardell believed that fashion was not something for the very few, whether they be very passionate or very wealthy or both. The purpose of the book, and McCardell’s clothes, too, was, as Burch put it, to help all women “feel more confident. And I think when clothes get too tricky or too precious—which I also love by the way, I’m not taking away from that—it’s not as understandable for some women. There’s nothing better for me to hear that when someone wears our collection, they feel more confident and they feel like a better version of themselves.”

Women today are busy, “as they were back in the forties and fifties, in a different way,” she continues. “But they don’t want to focus on just the way they look all the time. They want go out and they want to feel really chic and put together. That’s not a natural [gift] for some people. I think that to be able to solve those problems and offer people a collection where they can make it their own and mix and match it is something that I’ve always been interested in.”

That idea of clothing as a service for women feels novel even today, when it often feels like your only two options are Shein stan or fashion victim. As Burch put it, “It’s easy to forget how radical Claire was.”

You Might Also Like

[ad_2]

Source link