[ad_1]

This week marked this first time since 2012 that Pat Gelsinger has spoken at the annual Hot Chips conference. Gelsinger is the longtime Intel chief technology officer and former general manager of its Data Center Group, who learned the trade from Intel’s founders and who has returned to be its chief executive officer to turn the chip maker around.

Ten years ago, Gelsinger was in his third year as CEO of VMware after leaving Intel, his home for three decades – and he continued to beat the drum for X86 chips as ruling the datacenter. However, he also recognized that the IT environment was changing rapidly and that the cloud and mobile were where the action was going, big data was influencing hardware design and co-designing for hardware and software was becoming increasingly important.

Gelsinger returned to the virtual stage on the second day of Hot Chips, and a lot of things are different from what was anticipated ten years ago. Intel is still dominant in both the datacenter and PC markets – though less so than in previous years – but has sold off a lot of its software and memory businesses even as it has branched out into accelerators like FPGAs and GPUs and was pushing deeper into the cloud and out to the edge.

Intel is also participating in a much more competitive semiconductor market, with an ascendant AMD and a strengthening Arm, an Nvidia establishing itself as an increasingly critical datacenter player, and an environment of specialized silicon like data processing units (DPUs). IT suppliers, including Intel, are also suffering from pandemic-fueled supply chain problems and an uncertain global economy.

On top of all this, Intel has struggled to keep to its CPU roadmaps and has watched competitors pass it by in areas such as 7 nanometer and 5 nanometer process manufacturing.

Rather than push back from manufacturing, Gelsinger went all in, including investing $20 billion in new fabs and expanding its foundry business into a new business unit called Intel Foundry Services equal to other divisions in the company, complete with its own profit and loss statements.

It was this new foundry services business that Gelsinger focused on during his Hot Chips keynote, seeing it at as a key player in the continuing evolution of the IT space, where software is the central focus and hardware is there to ensure the performance and capabilities of the applications. The four technology superpowers are compute, connectivity, infrastructure and AI, all of which reinforce each other, he said.

“The more compute I have, the more I can do,” Gelsinger said. “The more infrastructure I have, the more data I can store, and the more data I have, the more learning and training I can do. Each reinforcing the other. That’s accelerating the pace. We see the superpowers increasingly allowing us to bridge from the physical to the digital worlds across literally every aspect of what we do. Underneath everything digital, powered by the superpowers, are the semiconductors. We’ve been in the era that more and more semiconductors are being enabled by the foundry business model.”

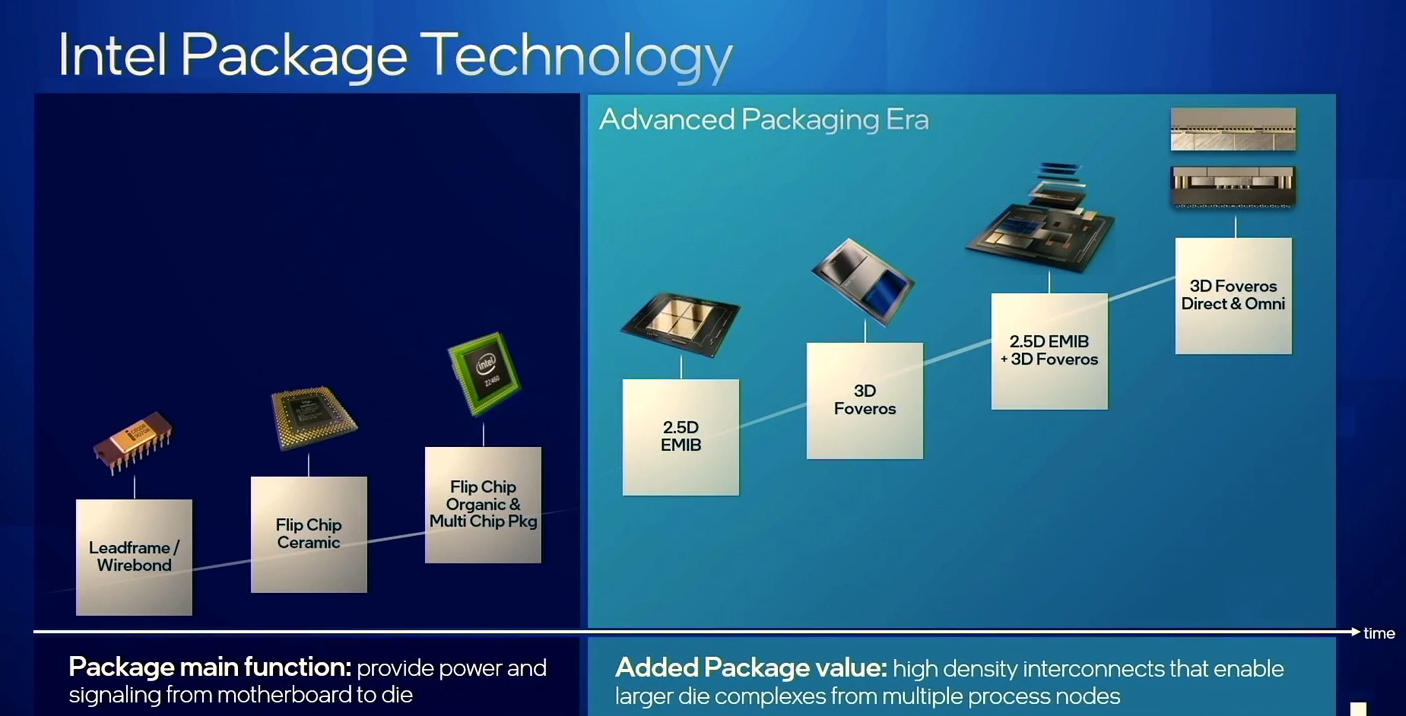

However, the idea of wafer foundry is giving way to the system foundry, with the rack becoming the system and the system a package of multiple dies and chiplets. More types of technologies are needed for 2.5 and 3D chiplet packaging, with chiplets and other IP coming together on the package to help create next-generation designs in a system foundry, which is what Gelsinger said Intel is aiming for – driving the ecosystem around these new technologies to enable designers to innovate at scale.

Unsurprisingly, Intel’s CEO sees Moore’s Law – which many industry observers see as slowing down – being foundational to all this. Gelsinger said there 100 billion transistors on packages today and that that will grow to 1 trillion by the end of the decade. He pointed to technologies like the RibbonFET transistor structure and Power VIA power delivery system unveiled last year by Intel and the use of High-NA EUV-lithography and 2.5 and 3D packaging as cutting the path toward 1 trillion transistors.

Other packaging technologies like Embedded Multi-die Interconnect Bridge (EBIM) to help tie more components together and Foveros for logic stacking will enable Intel to bring more functions into densely designed packages. New chips like “Meteor Lake” – due out next year – and after that “Arrow Lake” will take advantage of these technologies. The upcoming “Ponte Vecchio” GPU (which Gelsinger is holding in the feature image above), with its 47 active silicon tiles and more than 100 billion transistors on a single package, is as well.

What will be important going forward is standardizing in the industry how these different pieces are put together, not only within Intel but among other industry players. A key first step was the creation earlier this year of the Universal Chiplet Interconnect Express consortium to do for chiplets what PCI-Express interconnect standard did for tying peripherals into compute systems. Chip makers are creating processors that can pull different pieces together to make them less costly to make, more adaptable to the demands of software and able to meet the growing performance and throughput demands from compute and networking systems.

Joining Intel on the UCI-Express panel are vendors like AMD, Arm, Qualcomm (which reportedly is once again eyeing the datacenter), Microsoft, Meta and Samsung, along with TSMC and, most recently, Marvell.

“Now we’re doing [what was done with PCI-Express] at the chip level and taking a monolithic system on a chip that could be constrained in die size, cost and power, and being able to disaggregate it onto a solution that takes advantage of not only the advanced packaging, but the standard mix-and-match capabilities that UCIe will enable,” Gelsinger said. “Different process technologies will be optimized for different functions – power, RF, analog, advanced logic, memory. But we also will need to tie these together in a very easy-to-use composable fashion that gives the designers the abstractions that enable them to do more complex things without the detail of each execution and hardened IP at the lowest chip level.”

Enabling all this is being able to pull together different technologies found in disparate foundries. Gelsinger sees Intel Foundry Services as an open foundry, saying Intel can bring its foundry offerings to help drive the development of chiplets in the industry, with what he called the Intel Chiplet Studio Suite of technologies to enable it across not only x86 but other architectures, such as Arm and RISC-V.

He envisions chip designers to tap into technologies from a different foundries to build processors to address their specific needs. Like PCI-Express, UCI-Express will deliver a similar level of technology interchange.

“With that, you may say, ‘I’m getting two of the chiplets from Intel, I’m getting one of the chiplets coming from a TSMC factory,” Gelsinger said. “Maybe the power supply components are coming from TI, maybe there’s an I/O component coming from GlobalFoundries.’ And, of course, Intel has the best packaging technology, so they would be the one assembling all those chiplets together into the marketplace, but maybe it’s another provider as well. We do see the mix and match. When I say the rack is becoming a system, the system is becoming an advanced chiplet based on a package, that’s exactly what we mean, how we see it evolving.”

It won’t be easy. Intel will have to create a clean separation between its product businesses – which also will take advantage of the advanced packaging technologies offered in the foundry service – and outside companies using Intel’s foundry. In addition, the consortium also includes competitors, so – like other industry groups – that will have to be navigated.

Meanwhile, Intel has its own challenges. It has plans for new fabs in Ohio and Gelsinger was a key industry driver behind the $53 billion CHIPS Act signed by President Biden earlier this year that is designed to help fund more chip making in the United States. But as we explained last month, Intel has some operational and financial problems that while not impossible to fix, they are expensive And again, it comes at a time when companies like AMD and Arm that for years had their knives out for Intel are finally drawing blood and when top public cloud providers – which are the key customers for chip and systems makers – are more than willing to go their own way in designing their own processors.

[ad_2]

Source link