[ad_1]

One morning in September 2003, Jim E. Tynsky was working on the tip of a ridge above a canyon in southwestern Wyoming. That point of land had become known as “Tom’s Folly” because of a previous fossil hunter’s inability to find anything in the quarry there. Tynsky wasn’t doing much better. With the season racing to its snowy end, he had little to show for a summer of hard work but the commonest sort of fish fossils. Heaps of discarded stone slabs lay around like broken pottery.

Other quarries on this ridge were known for producing extraordinarily detailed and complete fossils, all from the bottom of an ancient lake. Tynsky, the third generation of his family to eke out a living from finding fossils there, knelt down beside a slab still embedded in the ground. He chose a spot along an exposed edge and started to work at it with his chisel and his geological hammer. A fragment of stone broke away above the split. He was expecting to find fossilized fish underneath. Maybe some good ones. What caught his eye instead was a foot.

He cleared a larger area, and the fossil began to take shape as a ghostly shadow across the newly exposed stone surface. It was humpbacked, and the size of a border collie, but with details obscured by the limestone matrix, as if painted over with cake batter. “I got something really cool over here,” Tynsky called out to a helper. “Might be a turtle, I don’t know.” He cleared a bit more and saw that the ordinary cracks in the stone had miraculously spared the fossil. The helper came over to look.

“Oh my God,” he said, after a moment. “You got a horse!” He started jumping up and down. “You got a horse! You got a horse!”

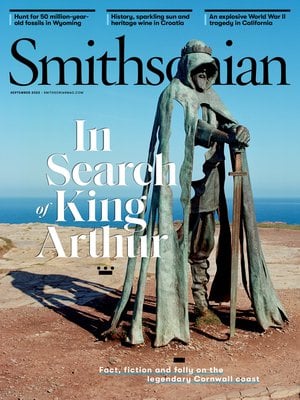

The “dawn horse,” discovered near Kemmerer, was a two-foot-long mammal that had legs suited to running from predators and teeth suggesting a leafy diet. Lucia RM Martino & James Di Loreto / Dept. of Paleobiology, SI

The bones all looked to be intact and attached in the right order. A peculiar little hind foot seemed to be kicking off one edge of the slab. The top of its eight-inch-long skull butted up against the opposite edge. The whole thing was around two feet long, and if that sounds small, it’s because this was a “dawn horse,” from the early history of the horse lineage, when all horses were about that size.

It was clear that the animal had died in a lake: A fish that had lived, died and been fossilized at the same time seemed to be leaping over the horse’s hips. Other fish swam through its abdomen and around its hind legs. For Tynsky, a season of just scraping by had suddenly lit up in bright gold. He had a hunch that this might just be the finest fossil ever produced from the Green River Formation, a 25,000-square-mile area of Wyoming, Utah and Colorado that is celebrated for producing some of the most beautiful fossils in the world. Any natural history museum would want it. So would a lot of private collectors. With help from nearby quarry operators, Tynsky carefully lifted his prize out of the ground and hauled it down to his double-wide in the nearby town of Kemmerer.

There, the horse would spend the next 15 years stabled in the laundry room.

Kemmerer (pronounced “Kemmer”) is a scrappy little community of 2,400 people, proud home to a sometime-state-champion high school football program and also to the “mother store” of the J.C. Penney retail chain, founded in 1902. A statue of James Cash Penney himself presides over the center of town, right hand held out as if for payment.

But geology has always been the real key to Kemmerer’s existence. You get a hint of that from a high looming mass called Oyster Ridge, which runs parallel to the town, and from the way subterranean forces seem to flex and shoulder their way across its thinly vegetated hillsides.

At Fossil Butte National Monument, a few miles out of town, curator Arvid Aase—imagine Bruce Willis as a geology teacher—delivered a lesson on the geological origin of the area, complete with sound effects. His right hand pushed across the back of his left to mimic “thrust sheets sliding in from the west—r-r-r-r-rrrrrrr.” These massive stone plates slowed down, he said, as their overlapping movement generated increasing friction—“u-u-u-r-r-r-r-r-RRRR.” Then his upper hand curved up, like a wave breaking, to mimic the leading edges of the thrust sheets pushing up to form Oyster Ridge and, a few miles behind it, a secondary ridge.

Fossil Butte National Monument: The site was established in 1972 to preserve “outstanding paleontological sites and related geological phenomena.” Taylor Glenn

Fifty million years ago, the Green RIver Formation was a thriving aquatic ecosystem. Now it’s an arid expanse rich in fossils. Smithsonian (Map Source: The Lost World of Fossil Lake, by Lance Grande)

In the 19th century, Kemmerer sprung up in the valley between the two ridges. The thrust plates had pushed coal from the Cretaceous era, more than 65 million years ago, up near the surface. From the 1880s on, underground coal mining became the town’s lifeblood and its heartbreak: An explosion in one mine killed 99 men a century ago next year. An explosion in another mine killed 39 a year later. The coal continues to come out of the ground today, not from underground mines but from a long black streak of strip mine in the second ridge, just outside town. That mine and the adjacent coal-fired power plant are still among Kemmerer’s top employers.

Geology had one other major effect, according to Aase, and it is the source of Kemmerer’s modern renown: The movement of the thrust sheets hollowed out a deep basin behind that second ridge. There, roughly 52 million years ago, Fossil Lake spread out across an area of about 1,500 square miles. It was part of a larger system of three great lakes, now called the Green River Formation. The dinosaurs had vanished, along with three-quarters of life on earth, in the mass extinction at the end of the Cretaceous, 65 million years earlier. So Fossil Lake flourished in the long post-apocalyptic recovery called the Eocene Epoch. Early modern mammals rose up then, liberated from dinosaur tyranny. So did modern birds, taking the place of the pterosaurs that had formerly ruled the skies.

The landscape around Kemmerer today is high plains desert, all sagebrush and exposed rock. But back then, said Aase, it was more like the Gulf Coast of Florida, warm, humid and abounding in life. The lake not only fostered wildlife but also routinely killed it in mass mortality events of uncertain origin. Low-oxygen water in the depths kept scavengers off the corpses long enough for calcium carbonate pouring down from the surrounding hills to preserve the remains in sedimentary layers resembling annual tree rings. As a result, the fossils tend to be intact and complete, and often beautiful enough to display on a wall like a work of art.

That’s a happy contrast with most other paleontological sites, where fossils turn up as higgledy-piggledy jigsaw puzzles and researchers must sometimes rely on a single tooth or a piece of jawbone to describe an entire species. At those digs, fossils also occur “here and there,” sporadically, said Lance Grande, an evolutionary biologist. They may have lived in the same place but 50,000 years apart. At Fossil Lake, on the other hand, the finely detailed layers contain “everything from micro-organisms to 20-foot crocodiles,” all of them having lived, and often died, at the same time.

Raw slabs are painstakingly cleaned in order to expose fossils. Here, Tynsky’s daughter, Stacey, works on a large crocodile that is partially exposed. Taylor Glenn

“You’ve got schools of fish, you’ve got babies and adults. You’ve got predators and prey together,” said Grande, a curator at the Field Museum in Chicago and author of The Lost World of Fossil Lake. It’s like “looking at a living community.” The result is “the best picture of life in the early Eocene that has ever been discovered.” It is a picture, in effect, of the beginning of the world as we know it.

One morning at the start of the summer season, with snow flurrying down and the temperature in the 30s, an earth science class from Eastern Connecticut State University arrived at the American Fossil Quarry, along the shore of the prehistoric lake. They had been traveling for the previous two weeks to study earthquakes, volcanoes, tectonics, rifting, faulting, folding and other major geological forces in the making of the Mountain West. But this last day of the trip was strictly for fun. A quarry guide handed out geological hammers and chisels and, with a few tips on safety and species identification, sent the students out into a field of lake-bottom rocks. The atmosphere at mid-morning was part prison gang, with the steady clink-clink-clink of rocks being split, but also part playground, with students plunked down in the dust, legs apart, pawing through the rock for treasure.

Dickson Cunningham, who teaches at Eastern Connecticut, at first declared no particular interest in fossils; he specializes in structural geology. But the hunt caught hold of him. “It’s kind of an addiction,” he mused, reaching for a rock. “Like panning for gold. Every rock has promise.” He split the rock and a decent-sized fish fossil emerged, but with half on one side of the split, half on the other. “Too bad I didn’t get the whole thing. It has a lot of detail.” He turned to the next rock. “It’s hard to stop. I can see how gold rushes start. It’s fossil fever here.”

Even the big rocks are surprisingly easy to split. (Easy, that is, after an excavator clears off 40 feet of hilltop overburden, a backhoe pulls big chunks of rock out of the fossil-rich layers of cliff face, and the newly exposed rock weathers in the sun for a day or two, or sometimes through several winters.)The technique is to start a hairline fracture with the chisel in the middle of an edge and extend it to the corner, easing the split along rather than forcing it. With luck and patience, the rock opens like a page of an illustrated book—a “Flintstones”-style page, on a slab a half-inch thick, revealing a 52-million-year-old picture of the living planet. What visitors mostly find are fossilized fish, their bones looking like the skeleton neatly picked from a freshly cooked trout.

A tourist at American Fossil Quarry uses a hammer and chisel to split shale rock to look for fossils. Taylor Glenn

A Diplomystus dentatus fossil in shale rock at American Fossil Quarry. Taylor Glenn

A half-dozen local quarries offer such digs to the public for an entry fee, in addition to their commercial work. Some allow digging in the “sandwich beds,” located mainly along the shoreline of the old lake. Other quarries offer pricier digs in “the 18-inch layer,” on Fossil Ridge, where the darker coloring makes fossils stand out better against the limestone. American Fossil, owned by two former educators, lets its customers take home whatever they find—though the staff strongly encourages selling or donating scientifically valuable specimens to a museum. Most other quarries reserve the “rares” for themselves, to sell or also sometimes donate.

In the Eastern Connecticut group, a student named Emily Watling had the magic touch. She split open a rock to reveal a fish called Phareodus, roughly a foot long. In commercial terms, it might be worth $1,500, an owner of American Fossil explained, though only after a preparator put in 20 hours at $60 an hour carefully picking off the matrix. He seemed happy to think the fossil might mean more than that to Watling, who carried her prize home the next day through airport security.

The spot where Jim Tynsky’s horse fossil turned up used to be known in the Lewis family not as “Tom’s Folly” but as “Nuisance Point,” because it blocked their view up the canyon from the ranch they homesteaded in the 1880s. The family ended up owning the point and a long stretch of Fossil Ridge by accident, after a 1908 federal survey relocated their property line a little north and west. The ridge was worthless for sheep grazing, their livelihood. But in the 1980s, Roland Lewis got a call from his mother to come home and save the ranch from ruin. He took an early retirement from the Forest Service, where he worked in finance, paid off the family’s overdue loans, and began to put the ranch back on solid footing. Many of the quarries on Fossil Ridge were just getting started then, and Lewis made sure the rising crop of operators paid adequate rent.

Seated in an overstuffed leather chair in a modern home across the highway from the cabin where he grew up, Lewis, now in his mid-80s, described the quarry operators with a certain ironic warmth as “my fossil family.” He has spent most of the past three decades dealing with a fair amount of bickering and maneuvering, as in other families. It can get “frustrating,” he said. Sometimes he might even get “owly” about it.

Lewis Ranch was once home to 46 cows and a family on the verge of bankruptcy. Then, in the 1980s, the family began leasing land to fossil hunters. Taylor Glenn

Roland Lewis remembers running around as a child, tinkering with rocks that might have held valuable fossils. Today, he’s an influential figure in the fossil business. Taylor Glenn

But the rising interest in fossils has also clearly changed life on the ranch, which now breeds and trains Arabian horses. Lewis wasn’t quite ready to say it had changed it for the better. But he thought back to his boyhood tending sheep up in Smith Hollow. When the sheep headed off the wrong way, he said, “I pulled up a rock and rolled it down the hill” to turn them around. Then he grinned broadly. “It’s a helluva lot better than that.”

Lewis became deeply engaged in the business, particularly in determining where a rare fossil would sell, and for how much, with up to half the money due to him as landowner. Tynsky’s horse, with the limestone coating carefully cleaned off by a preparator, quickly attracted a $1 million offer, rumored to be from the Field Museum. Lewis, having read up on recent dinosaur sales, thought it should be worth eight times that amount.

“That’s what he wanted,” Tynsky recalled with a shrug, back at work recently on Fossil Ridge. “I thought, well, I’ll just put it aside, see if anybody wants to pay the price. But I won’t count on selling it. I wanted to see it go to a good place, you know.” Meanwhile, Tynsky locked it in his laundry room, in a fireproof box. He couldn’t afford to insure it, and that “worried me a lot,” he said.

Rick Hebdon uses a stone saw to isolate a fossil during a night dig at his quarry on fossil ridge.

Taylor Glenn

A quirk in the psychology of fossil hunters is that they often balk at selling their best specimens. “One of my weaknesses,” said Rick Hebdon, at Warfield Fossils, next door to American Fossil, “is that I have been my own best customer forever. I’d sell what I needed to, to keep the money coming in. And the really good stuff I kept.” A related quirk is that, while they are ostensibly in it for the money, fossil hunters generally like their best specimens to end up in a museum, even if it means a lower price. Fossil Butte National Monument, just outside of town, is at the top of their list, because they can take their grandchildren there and talk about the time they split the rock that became the museum display. So is the Field Museum, because Lance Grande has assembled the world’s best collection of Fossil Lake specimens.

For years, Hebdon hoarded a fossil lizard, a pregnant stingray, assorted mammals and birds and “a lot of different things” until one day something shifted and he sold the whole lot to the Field Museum. It’s a bragging point for him now that his specimens are on display there, and that his lizard made the cover of Grande’s Lost World of Fossil Lake. “I’ve got eight holotypes,” said Hebdon, meaning specimens by which a new species was first described, “and five paratypes,” meaning specimens that are better than the one on which a species was originally described. “When they get done with all the birds,” he said, “I’ll be up in the teens with holotypes.”

A fat-tail stingray fossil found in the quarries near Kemmerer. A small stingray fetus can be clearly seen curled up inside this female’s body. Lance Grande

A find from Fossil Lake shows that prehistoric songbirds were similar to their modern descendants, though they had different numbers of toes in front and back. ©The Field Museum, D. Scher

Meanwhile, thinking about the horse in the laundry room, Tynsky said, “I’d go and look at it once in a while. I loved it.” Pressed to explain why, he added, “Because it was the neatest thing I ever found in my life. Probably the best fossil ever found, that I know of.” It was a horse, but also different, not just in size but with three toes on its hind feet and four on the front instead of hooves. Those kinds of quirks are typical of the Eocene, according to Steve Brusatte, a University of Edinburgh paleontologist and author of The Rise and Reign of the Mammals. “It’s where we start to see a lot of mammals that make sense, mammals whose faces and frames and features we recognize. We see obvious horses, bats, whales and primates. But they don’t quite fit the image of today’s mammals. It’s like viewing a horse or a primate through a fun house mirror. They seem different, a bit distorted.”

The first songbirds, forerunners of the largest group of modern birds, appeared then, also in a “what’s-wrong-with-this-picture” way. Modern songbirds typically have three toes pointing forward, and one back, an adaptation for their perching way of life, and for building nests in wildly varied locations. But early songbirds from Fossil Lake mostly had two toes forward and two back, like modern woodpeckers, suggesting that they may have evolved as tree-cavity nesters.

The fish are likewise often weirdly different from their modern counterparts. Modern gars, for instance, have pointy mouths with sharp teeth for preying on other fish. But one Fossil Lake gar is blunt-nosed and with knobby teeth like molars. Other fish “show trans-Pacific relationships rather than trans-Atlantic,” said Lance Grande. Some are more closely related to species on the other side of the Pacific than they are to the North American fishes on the eastern side of the Rocky Mountains, 200 miles away. The Phareodus that student carried home to Eastern Connecticut, for instance, had its closest cousin in Queensland, Australia. “That is a historic remnant of the fact that the continents used to be connected,” Grande said.

A fossil of icaronycteris, one of the first bats known to science, was discovered in in the Fossil Butte area. ©The Field Museum, D. Scher

An illustration of what Icaronycteris might have looked like Correy Ford / Alamy Stock Photo

But it is the horse and the fun house differences in its Eocene lineage that have played the biggest part in the story of evolution. For more than a century, beginning in the 1870s, the development of the North American horse was a standard science lesson, illustrating how evolution seemed to progress in an orderly ladderlike fashion from four-, to three-, to two-toed species, culminating finally in the hoofed modern horse. You can still sometimes see that idea diagrammed in natural history museums, with teeth as well as feet evolving toward the modern form.

Field Museum curator Lance Grande, far left, specializes in the evolution of ray-finned fishes. He has led dozens of fossil-finding expeditions in Wyoming and nearby areas. Taylor Glenn

But scholars have junked the idea that evolution is progressive. Instead of a ladder, evolution now looks more like a “tree of relationships,” said Grande, with many branches and many dead ends. In place of the idea that species evolve into more perfect forms, the multi-toed horse might simply have been a more suitable form around the marshy perimeter of Fossil Lake, while the hoofed horse is suitable for carrying its massive form quickly across the dry, hard surfaces of many modern habitats. That’s not to say that one evolved into the other, or much else about what happened in between, said Grande, because it’s hard to make precise observations about periods of time that are 1,000 years long, much less 52 million. In any case, all North American horse species ultimately went extinct. Modern horses only arrived on the continent with Christopher Columbus in 1493, and their evolutionary connection to early American horses remains a topic of continuing debate.

Tynsky’s horse raised one other enduring question: How the heck did a horse end up in the middle of a ten-mile-wide lake? It is a subject Kemmerer fossil folks still like to chew on two decades after the discovery. One quarry operator speculated that a large predatory bird plucked up the horse, like a modern eagle grabbing a fox, and lost control in the struggle over the lake. But Arvid Aase at Fossil Butte National Monument scoffed at this idea. He walked around to a bird exhibit and pointed to a ten-inch-long feather, from the largest bird known to exist in the area at that time. It was a Gastornis, also known as “the terror bird.” But it was flightless, and its jaws were built for cracking and eating nuts, not horses. He theorized that the unlucky horse tried to cross a tributary stream in flood stage and got swept out into the lake to drown.

Anthony Lindgren, who operates a quarry a hundred yards from where Tynsky found his horse, proposed a third theory: Maybe this bit of Fossil Ridge wasn’t in the middle of the lake after all, he said, but along the old shoreline, where a horse might reasonably have waded out to drink. In the same stratigraphic layer that produced the horse, there’s an abundant fish mass mortality event. That’s commonplace for Fossil Lake. But Lindgren has also found evidence of dozens of bubbles—he spread his hands apart—“18 inches across.” He theorized that seismic activity caused a carbon dioxide eruption, killing horse and fish at the same moment. That sort of disaster still sometimes happens: In 1986, a methane eruption at a lake in the West African nation of Cameroon killed more than 1,700 people and their livestock. But Lindgren is still waiting for a paleontologist to show up and confirm that it happened at Fossil Lake.

Tynsky himself had no theories. Instead, humbler domestic considerations ultimately led him to let the horse out of the laundry room. “I wasn’t really pushing to sell it,” he said. “I don’t know what happened. My wife was like, ‘We need to sell it. We need to pay some bills.’” So in 2018, he packed up his great prize and took it to Tucson, where the world’s largest fossil and gem show sprawls across the city every year. Arvid Aase naturally coveted the horse for Fossil Butte National Monument. But he couldn’t afford the price. Instead, he alerted a friend.

Tynsky, discoverer of the spectacular horse fossil, comes from a rock-hound lineage: His grandfather Sylvester opened a fossil quarry in the 1960s. Taylor Glenn

Kirk Johnson, a paleobotanist, knew Tynsky’s find from photographs and by reputation. In his 2007 book, Cruisin’ the Fossil Freeway, an account of travels among the fossil digs and “paleonerds” of the American West, Johnson described the horse laid out “as though it were sleeping,” its “chocolaty brown bones” on a creamy slab “sprinkled with fossil fish in a sweet little surf-and-turf composition.” At the time, Tynsky was being discreet about the laundry room, and Johnson thought “this fine fossil was residing in a bank vault in downtown Kemmerer.” He noted that “the market has always lusted for these rare beauties.” But Johnson, then at the Denver Museum of Nature and Science, wasn’t in the market at the time, at least not at the rumored price level.

By 2018, though, Johnson had become director of Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History, where he was helping to put together a new “Deep Time” exhibition. “I don’t know how it all happened,” said Tynsky. “But Kirk called me and said he was very interested in it.” It took another seven months, with Johnson working on an anonymous donor and Tynsky consulting with Roland Lewis. “I loved it,” Tynsky repeated. “If I was rich, I would have never sold it, guaranteed.” He might have put it on loan to Fossil Butte National Monument, “where I could go out and look at it.” But he rationalized: “It’s in a good place right now, Smithsonian. What is it, like a million people a year go through there? They take care of it.” The money would allow him to pay off the mortgage on his house and live a bit more comfortably. For Lewis, the price, in the high six figures, was the sticking point. “I really had misgivings of letting it go that low,” he said. “But I thought, ‘Well, now that Smithsonian is finally interested, that’s where it should be.’”

The horse slipped into the “Deep Time” exhibit just before it opened in 2019. According to Johnson, more like five million people see it every year in its new home. Among them is Tynsky’s stepdaughter, a schoolteacher, who has sometimes taken her class there. Tynsky himself hasn’t visited, but he sometimes goes on FaceTime to chat with the kids about his find. He’s 71 now, with a grip that’s still powerful but prone to arthritis, as are his knees. Lately, he has also been undergoing chemotherapy and radiation treatment for cancer. The only travel that still interests him is from his home in Kemmerer to the quarry and back home again to wash off the dust. He was up on Fossil Ridge the other day, chisel and hammer in hand, splitting a slab of rock to expose a nice mass mortality event, hoping as always for the next great treasure.

Recommended Videos

[ad_2]

Source link