[ad_1]

This weekend marked the return of one of Central New York’s most unique art and cultural institutions, “Shakespeare in the Park,” which celebrates its 20th anniversary this year.

Over the last two decades, the program has brought the legendary English playwright’s work to life on the stage employing ensemble casts of predominately child and senior citizen actors, on sets and in costumes that harken back to Shakespeare’s own time.

While the plays and the casts have changed over these many years, the omnipresent star of every show is the setting, Syracuse’s beloved Thornden Park and its beautiful amphitheater.

Now, Thornden has hosted Shakespeare in the Park for two decades, yes, but the park has been far more than just a setting for Shakespearean fiction. In fact, Thornden Park has its origins in a series of real-life dramas that give even the Bard a run for his pounds, shillings, and pence.

The story of Thornden Park begins with a visionary and enterprising man named James Haskins.

Born on a farm in Pompey in 1814, Haskins moved to Salina in 1827 and became a clerk in a grocery store.

Just over three decades since the first white settlers came to this land stewarded by the Haudenosaunee for centuries, and just two years after the completion of the Erie Canal, the village of Salina had grown into a sizable community centered around the exponentially expanding salt industry.

While working as a grocer and a clerk, Haskins soaked up all of the knowledge that he could about the salt business, recognizing, like many others flocking to the area, the incredible wealth offered by the region’s vast quantities of “white gold.”

– Thornden, circa 1900. After being abandoned by the Davis family, David Campbell, the head gardener, stayed on and managed the property for several years. Upon the death of Davis’s widow in 1920, the city of Syracuse purchased the property and turned it into a park. Tragically, the house burned to the ground in 1929, having just undergone extensive renovations. Onondaga Historical AssociationOnondaga Historical Association

By 1840, he had immersed himself in the industry and in 1843 he built the first large scale salt mill on the Salt Springs Reservation. In 1845, Haskins suffered two nearly simultaneous tragedies. In March, his beloved wife, Caroline, died while giving birth to the couple’s first child, who also did not survive. It was said that Haskins never recovered from the unimaginable loss.

A few months later, his mill burned to the ground.

These almost unbearable calamities coming in quick succession hardened Haskins’s resolve and he threw himself into business, where he had already built up a formidable reputation for pugnacity.

Haskins began a meteoric rise that catapulted him into the highest echelon of the city’s elite.

Beginning in 1850, he built nine salt blocks in the marshlands in the First Ward. In 1852, Haskins was awarded a patent for a new technique for purifying salt and was also a founder of the Onondaga Fine Salt Company.

His significant holdings in the salt industry gave rise to another source of incredible wealth, as Haskins became the principal investor in the Morris Run Coal Company, based in Pennsylvania.

This was a particularly shrewd business move.

After nearly four decades of incessant growth, the area had been almost totally deforested, greatly increasing the fuel costs for salt block operation. Haskins’s move into the coal business gave him both a new lucrative source of wealth and a competitive advantage over many of his competitors.

While his intense focus on business led to tremendous success, in his personal life Haskins lived like a recluse. In the wake of the loss of his wife and child, he sought solitude and seclusion. As such, he used his immense wealth to manifest a world of his own on a plot of land on the eastern edge of the burgeoning city of Syracuse.

Sometime around 1850, Haskins purchased approximately fifty acres of land from farmer, Zebulon Ostrom, adjoining his holdings near Beech and Madison Streets.

Over the ensuing years, Haskins bought up more of the property in the area, eventually amassing over one hundred acres. He gave the property over to a series of gardeners, who set to work turning the former farmland into a menagerie of flowers, trees, and shrubberies.

By 1854, Haskins erected a beautiful Victorian structure on the property, which initially served as both a gardener’s cottage and his home. Haskins made various additions to his house over the years and it eventually grew into a sizable mansion where he could stroll the grounds with his dog, his constant companion.

Haskins’s eccentric manner, great wealth and landed estate, made him quite a curiosity in the Salt City.

In the early 1860s, Haskins hired a gardener, William Harradence, to manage the property. Harradence opened up a nursery on the site where he sold a variety of fruit and ornamental trees, grape vines, shrubs, and a wide array of roses, foreshadowing the E.M. Mills Rose Garden.

According to a piece published in the “Syracuse Journal” in April 1866, Harradence’s work and nursery on the “beautiful grounds of Mr. J.P. Haskins, in the eastern part of the city, are attracting the attention our citizens interested in such manners.”

The anonymous author was effusive in his praise of the “ornamental trees and shrubbery with which Mr. Haskins has so tastefully and liberally decorated his grounds…to strolling an hour or two among them, and enjoy the magnificent views spread out all around…is of itself worth a day’s journey.”

Hawkins, it seems, had succeeded in manifesting splendid beauty and peaceful serenity from the horrific tragedy that had nearly consumed him in 1845.

Alas, this was not the case.

On the morning of Jan. 27, 1873, Haskins was found barely conscious in the bathtub of his home by his personal attendant James Webb, and noted local physician, Dr. Henry Didama, Haskins’s good friend, covered in blood with his throat slit from ear to ear in an apparent attempted suicide. Somehow, he managed to hold on to life for a few days before succumbing on January 30.

He was buried in Oakwood Cemetery.

As the news of his suicide spread like wild fire through the city, speculation ran rampant that the reclusive and melancholy millionaire had chosen to reunite with his wife and child in the afterlife, having mourned them for nearly three decades.

Others offered a more prosaic financial explanation. Whatever the cause, Haskins’s fortune turned out to have been greatly diminished and it took nearly two years to settle his estate. On July 28, 1875, Major Alexander Davis, purchased the mortgage to Haskin’s property for $74,500 ($1.9 million in 2022).

Over the next 13 years, Davis, a native-born Syracusan and son of former Congressman who had been a business associate of Haskins, spent a small fortune expanding the mansion, decorating it with priceless works of art collected over years of extravagant travel, and adding to the grounds.

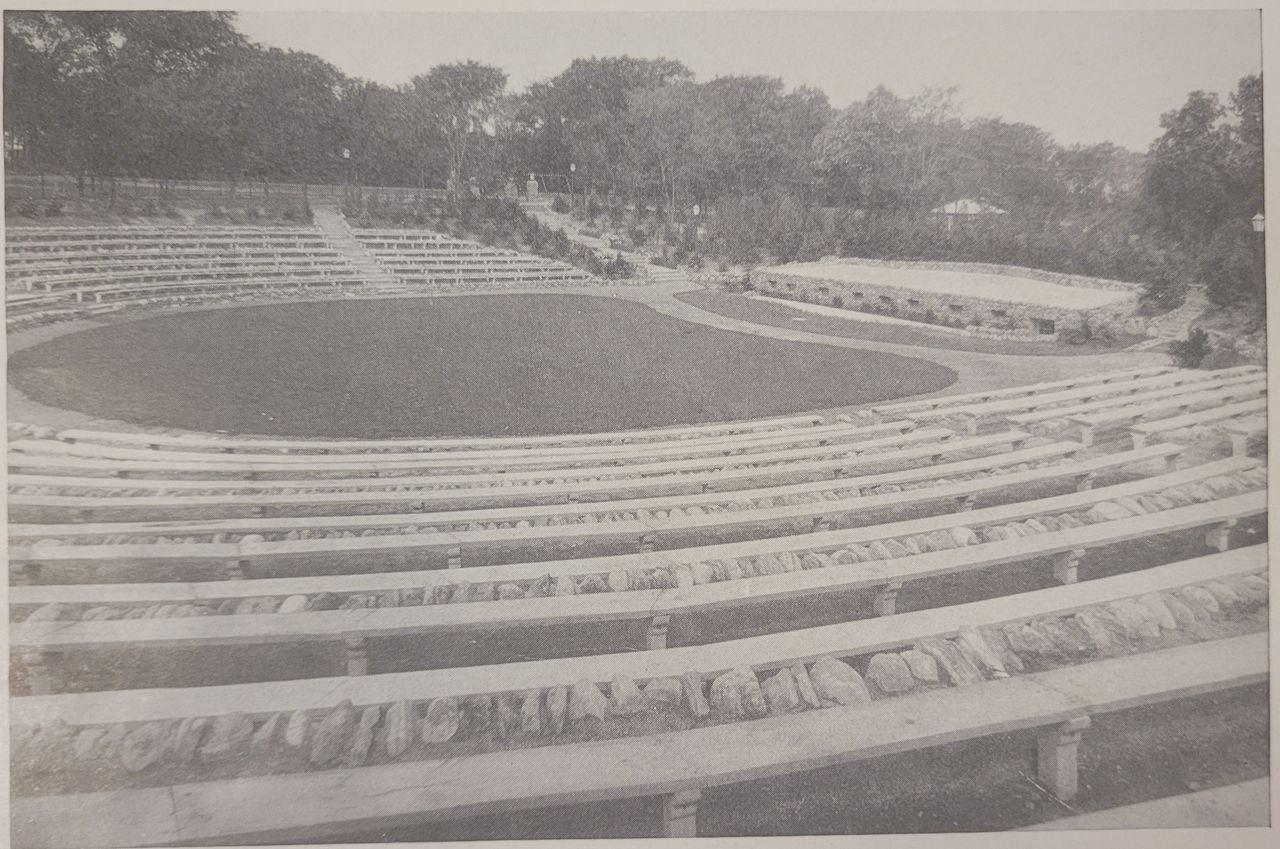

– Thornden Park Amphitheater In Syracuse shortly after it was completed in 1933. Onondaga Historical AssociationOnondaga Historical Association

He had fallen in love with the property on a visit a few years before. An unparalleled Anglophile, Davis fancied himself a true English gentleman, and, as such, he desired a landed estate. He built a reserve for deer hunting and the city’s first golf course, in 1885.

He named it Thornden.

There, Davis and his wife, Caroline, threw some of the most lavish parties and balls the city of Syracuse had ever witnessed and entertained guests from around the world.

After running for Congress and losing in 1888, Davis decided to abandon Thornden, splitting time between England and his “Villa Floridiana,” in Naples.

He was joined by his wife and two daughters in 1900. In 1901, Davis became a subject of Edward VII, making his transformation into English gentleman complete.

Just imagine how delighted Major. Davis would be to know that the inimitable works of William Shakespeare are being acted out on the site of his former fishing pond!

[ad_2]

Source link